Navigation & Star Maps

Aboriginal Australians use the stars to navigate across the continent. Thesis accomplished in many ways, including following particular stars or developing maps of the stars that correlate to landscape features.

Aboriginal Australians use the stars to navigate across the continent. Thesis accomplished in many ways, including following particular stars or developing maps of the stars that correlate to landscape features.

The concept of cardinal directions is common amongst Aboriginal language groups in Australia. The Warlpiri people in central Australia are especially prominent in this respect, as much of their culture is based on the four cardinal directions that correspond closely to the four cardinal points (North, South, East, West) of modern Western culture. In the Warlpiri culture, north corresponds to “law”, south to “ceremony”, west to “language”, and east to “skin”. “Country” lies at the intersection of these directions, at the centre of the compass – i.e. “here”.

Cardinal directions are also important in Wardaman culture, and were created in the Dreaming by the Blue-tongued Lizard:

“Blue-tongue Lungarra now he showing all these boomerang, calling out all the names: east, west, north, south, all these sort of type.” – Bill Yidumduma Harney, Wardaman Elder

Directionality is also important in the sleeping position, as described by Uncle Yidumduma:

“We gotta sleep east, not downhill. We can sleep crossway, but we’re not allowed to sleep towards the sun going down. Sleep down the bottom, its bad luck for you because you’re against the sun. If you sleep on the eastern way and going that away, that’s fine. Facing west, you gotta change your bed. Head up on the east when you sleep … each person where they die, in our Law, we always face them to their country. Graveyard always face to their country, they can look straight to their country.”

The three major creation figures (Froglady Earthmother and her two husbands, Rainbow and Sky Boss) are all signified by dark clouds in the Milky Way, and stars and nebulae document other figures and other events. The Southern Cross is particularly important, and its orientation defines the Wardaman calendar and marks the cycle of dreaming stories throughout the year.

In the words of Uncle Yidumduma:

“In the country the landscape, the walking and dark on foot all around the country in the long grass, spearing, hunting, gathering with our Mum and all this but each night where we were going to travel back to the camp otherwise you don’t get lost and all the only tell was about a star. How to travel? Follow the star along. … While we were growing up. We only lay on our back and talk about the stars. We talk about emus and kangaroos, the whole and the stars, the turkeys and the willy wagtail, the whole lot, everything up in the star we named them all with Aboriginal names. Anyway we talked about a lot of that … but we didn’t have a watch in those days. We always followed the star for the watch. … Emu, Crocodile, Cat Fish, Eagle Hawk, and all in the sky in one of the stars. The stars and the Milky Way have been moving all around. If you lay on your back in the middle of the night you can see the stars all blinking. They’re all talking.”

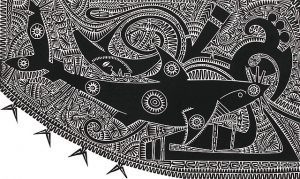

The Torres Strait Islanders use stars to navigate, particularly the great shark (Baidam) and the left hand of Tagai, Crux (the Southern Cross). The gills of the shark point to North while the stars of Crux point to the South.

Star Maps

Robert Fuller, an MPhil student at Macquarie University) was researching the astronomical knowledge of the Euahlayi and Kamilaroi Aboriginal peoples of northwest New South Wales in 2013 when he became aware of “star maps” as a means of teaching navigation outside of one’s own local country. His teacher of this knowledge was Ghillar Michael Anderson, a Euahlayi Culture Man from Goodooga, near the Queensland border. This is where the western plains and the star-filled night sky meet in a seamless and profound display.

One night, sitting under those stars in Goodooga, Uncle Ghillar pointed out a pattern of stars to the southeast, and said that they were used to teach Euahlayi travellers how to navigate outside their own country during the summer travel season. Robert immediately realised that those stars were not in the direction of travel that Uncle Ghillar was describing. And anyway, they wouldn’t be visible in the summer, let alone during the day when people would have been travelling. Uncle Ghillar said that they weren’t used as a map as such, but were used as a memory aid. And in the Aboriginal manner of teaching, he asked Robert to research this and come back to see if “I had gotten it”.

Robert did some research, and looked at a route from Goodooga to the Bunya Mountains northwest of Brisbane, where an Aboriginal Bunya nut festival was held every three years until disrupted by European invasion. It turned out the pattern of stars showed the “waypoints” on the route. These waypoints were usually waterholes or turning places on the landscape. These waypoints were used in a very similar way to navigating with a GPS, where waypoints are also used as stopping or turning points.

Stars to songlines

Further discussion revealed the reasons and methods of this technique. In the winter camp, when the summer travel was being planned in August or September, a person who had travelled the intended route was tasked with teaching others, who had not made this journey, how to navigate to the intended destination. The pattern of stars (the “star map”) was used as a memory aid in teaching the route and the waypoints to the destination. After more research Robert asked Uncle Ghillar if the method of teaching and memorising was by song, as he was aware that songs are known to be an effective way of memorising a sequence in the oral transmission of knowledge.

Uncle Ghillar said, “you got it!”, and Robert then understood that the very process of creating, then teaching, such a route resulted in what is known as a songline. A songline is a story that travels over the landscape, which is then imprinted with the song (Aboriginal people will say that the landscape imprints the song). Robert then learned that there were many routes/songlines from Goodooga to destinations as far as 700km away, which might end up in a ceremonial place, or possibly a trade “fair”.

One such route to Quilpie, in Queensland, led to a ceremonial place where Arrernte people from north of Alice Springs met the Euahlayi for joint ceremonies. Their route of travel was more than 1,500km, crossing the Simpson Desert in summer, and Robert was told that they would have their own star map/songline for learning that route. The implication of this is that the use of star maps for teaching travel may have been common across Australia.

Parallels

Another surprising result of this knowledge came about when Robert was looking at the star map routes from Goodooga to the Bunya Mountains and Carnarvon Gorge in Queensland. When the star map routes were overlaid over the modern road map, there was a significant overlap with major roads in use today. After some reflection, the reason for this became clear. The first explorers in this region, such as Thomas Mitchell, who explored here in 1845-1846, used Aboriginal guides and interpreters, who were likely given directions by local Aboriginal people.

These directions would no doubt reflect the easiest routes to traverse, and these were probably routes already established as songlines. Drovers and settlers coming into the region would have used the same routes, and eventually these became tracks and finally highways. In a sense, the Aboriginal people of Australia had a big part in the layout of the modern Australian road network. And in some cases, such as the Kamilaroi Highway running from the Hunter Valley to Bourke in NSW, this has been recognised in the name.

Published Research

- Norris, R.P. (2016). Dawes Review 5: Australian Aboriginal Astronomy and Navigation. Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia, Vol. 33, e039.

- Norris, R.P. and Harney, B.Y. (2014). Songlines and navigation in Wardaman and other Australian Aboriginal cultures. Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, Vol. 17(2), pp. 141–148.

- Fuller, R.S., Trudgett, M.M., Norris, R.P., and Anderson, M.G. (2014). Star maps and travelling to ceremonies: the Euahlayi People and their use of the night sky. Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, Vol. 17(2), pp. 149–160, 2014.

- Hamacher, D.W., Fuller, R.S., and Norris, R.P. (2012). Orientations of Linear Stone Arrangements in New South Wales. Australian Archaeology, No. 75, pp. 46-54.